Genomic and phenotypic patterns of polygenic adaptation

The majority of quantitative traits are under stabilizing selection, which stabilizes the population mean on a specific average trait value, known as the trait optimum. Environmental changes cause a shift in the trait optimum, and the population responds by a rapid shift of the trait mean to match the new optimum. After the new optimum is reached, the trait mean does not change. But what is the genetic basis of this phenotypic change?

Theoretical models (1) and simulations (2) predict that adaptation of quantitative traits after a shift in trait optimum has several stages. In the first stage, right after a shift in the trait optimum, the trait mean changes towards the new optimum. This change is accompanied by the frequency increase of adaptive alleles (directional selection). In the next stage, after the new trait optimum is reached, the trait stabilizes on the new mean and the allele frequencies plateau before fixation and loss (stabilizing selection).

Our computer simulations (3) show that the temporal pattern of phenotypic change can be used to distinguish different stages of polygenic adaptation. In this project, we take advantage of the temporal phenotypic data to identify different stages of adaptation and determine when the new trait optimum is reached. In larger populations, adaptation is faster, which allows us to have a clearer pattern of polygenic adaptation (3).

Fig.1 Mean phenotype after a shift in optimum Mean phenotype changes after the shift, but once the new optimum is reached, the mean phenotype does not change. Populations of 450 (solid lines) and 9,000 (dotted lines) individuals were simulated. Lines depict the median phenotype averaged across 500 replicates and the shaded areas show standard deviation. The optimum phenotype is 1.1, and populations reach the new trait optimum around generation 40. Figures from (3).

We implemented a laboratory natural selection experiment in which we exposed replicate populations of Drosophila simulans in large (100,000 individuals) and small populations (800 individuals) to a new selection regime that is a high protein diet. Using time-series transcriptomic, metabolomic and highorder phenotypic data we determine when the experimental populations have reached the optimal phenotype in this new environment. The information about the time that optimal phenotype is reached will allow us to identify adaptive alleles in the directional selection phase, and to study the dynamics of allele frequencies at the stabilizing selection phase using genomic data.

References

Adaptive architecture of polygenic traits

Recently, many theoretical studies (1-4) investigated the adaptive response of a quantitative trait under stabilizing selection after a shift in its optimum. However, empirical data for such adaptive response are rare as in most natural and experimental populations the focal trait under selection is not known Determining the selected trait and phenotyping the natural populations is challenging. But experimental evolution offers a powerful, thus far unexploited, method to shift the optimum for a trait under stabilizing selection.

In this project, we will, for the first time, perform an experiment where populations adapt to a new trait optimum where the shift in optimum is experimentally defined. Using Drosophila simulans we will shift the female body size, a well-defined and highly heritable trait, toward larger size. Using temporal genomic and phenotypic data in replicate populations, we will characterize the alleles responsible for adaptation of large body size in females, i.e. adaptive architecture, and provide empirical data for adaptive processes of polygenic traits.

Fig. 1 Shift of female body size toward larger size in E&R . The fitness function for shifting the mean female body size is chosen to increase the female body size by 15% of the size in founder population (green line). For each replicate, females contributing to the next generation will be chosen according to the new fitness function (red line).

References

Genetic architecture of complex and quantitative traits

Many GWA (1,2) studies investigated the genetic architecture of polygenic traits and identified many underlying alleles. The genetic architecture of quantitative traits comprises of all the contributing alleles and their effect sizes. However, only a subset of the underlying alleles responds to selection, i.e. the adaptive architecture (3). Factors such as the distance to the new trait optimum, starting frequencies and pleiotropy determine which alleles are potentially adaptive.

The aim of this project is to determine the genetic architecture of a polygenic trait, Drosophila simulans female body size, using a GWAS with 2000 heterozygous individuals. We will compare the genetic architectures of female body size characterized in this project with the adaptive architecture of this trait identified in a parallel project where Drosophila simulans populations are experimentally evolved for larger body size. The availability of this data set allows us to distinguish alleles with adaptive potential from alleles with constraints.

References

The extent of genetic redundancy in polygenic adaptation

Genetic redundancy facilitates adaptation and is an important characteristic of polygenic adaptation (1,2). But it is not understood how redundancy manifests at different hierarchal levels such as genomic, gene expression, metabolites, or high-order phenotypes during adaptation. Phenotypic convergence in replicate populations with hetero geneous genomic responses (1) suggests that the extent of redundancy decreases as the biological hierarchy is higher, i.e. redundancy decreases from genetic variants to the high-order phenotypes.

We have developed an accurate and high throughput method for embryo size measurement using flow cytometry (3) that allows performing selection experiments by sorting viable Drosophila embryos from any specified size range. Using this method, we have established an experimental framework to shift the optimum of Drosophila embryo size towards bigger size with different intensities, i.e. different new trait optima, in replicate populations. Given the unique design of this experiment, we can infer redundancy by estimating parallelism at different hierarchical levels by comparing selected alleles, differentially expressed genes, differential metabolites, and high-order phenotypes.

Fig. 1 The interplay of redundancy, parallelism and distance to the new trait optimum. Redundancy results in the contribution of different sets of alleles to adaptation in replicate populations, i.e. non-parallelism, so parallelism can be used as a proxy for redundancy. The extent of redundancy depends on the distance to the new optimum.

References

The effect of optimum shift intensity on the molecular patterns of adaptation

The characteristics of alleles that are involved in adaptation of complex traits are affected by a number of factors. The intensity of shift in the trait optimum is an important factor that influences the adaptive response of populations (1-3). However, the selected trait and intensity of the shift in trait optimum in many experimental and natural populations is unknown. Using the accurate and high through put method that we have developed for embryo size measurement using flow cytometry (4), we perform selection experiments where we shift the optimum of Drosophila embryo size towards bigger size with different intensities, i.e. different new trait optima, in replicate populations. This allows us to dissect the effect of the intensity of optimum shift on adaptive architecture.

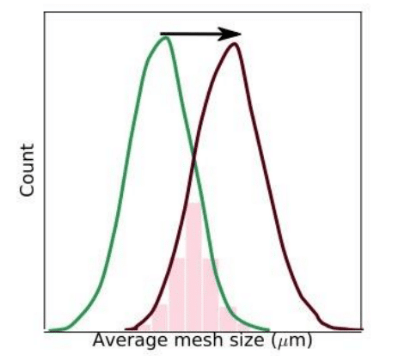

Fig. 1 Experimental framework to shift the optimum of Drosophila embryo size. The fitness functions to increase the average embryo size by 1.5, 2.5, and 3.5 (pink, red, maroon lines) standard deviation of the egg size distribution in the founder population (green line).

The unique design of this experiment allows us to estimate the contribution of selected alleles (effect size) to the change in the average trait, i.e. embryo size, in the replicate populations with different in tensities of optima shifts. Based on theoretical predictions(1,5,6) we expect the contribution of many small-effect alleles to adaptation when the new trait optimum is close. However, large-effect alleles will be favored when the new optimum is farther. The results of this project will provide the first empirical data to show how the adaptive signatures of a trait change as a result of the intensity of the trait optimum shift.

References

Coming Soon